Engaging a Wider Community: Awareness, Education, and Support

Hearing plays a vital role in how individuals experience, interact with, and relate to the people and environment around them. Hearing is sometimes referred to as the “social sense” because of its function in developing and maintaining intimate relationships and social connections with family, friends, coworkers, and acquaintances. As described in Chapter 1, the social-ecological model depicts the complex network that encompasses the interplay among individuals and their families, the social networks and relationships in their lives, the organizations and institutions that provide services and support to the individuals, the communities in which the individuals work and live, and society at large. Supporting individuals with hearing loss requires adaptable solutions that span society—not just solutions geared toward individuals with hearing loss or solutions within the context of a medical model that revolves around the delivery of care and services in a health care setting. Components at all levels of the social-ecological model can contribute to hearing health and overall well-being.

This chapter focuses on education, support, and awareness for individuals with hearing loss, their families, their communities, and society as a whole. Attitudes and beliefs about hearing loss and the use of hearing health care services and technologies are explored from the perspectives of individuals and family members, employers and coworkers, and the general public, including the media. The chapter provides insights on the role of health literacy, the Internet, community-based support, and the built environment, such as public and private spaces that can be designed or altered to enhance acoustics and accessibility, and it also describes how these factors can empower individuals with hearing loss. The chapter also examines the role of the community, organizations, and the public in supporting individuals with hearing loss and considers whether attitudes about hearing loss have improvwith the increasing use of technology, specifically mobile technologies. Finally, the chapter highlights areas of focus for next steps as well as research priorities that are essential for optimizing support and access for individuals with hearing loss.

Although the knowledge, attitudes, education initiatives, and community support associated with other health conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, epilepsy, cancer, and substance use and mental health, have been well studied and are thoroughly described in published, peer-reviewed literature and in previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports (e.g., IOM, 2006, 2012; IOM and NRC, 2005), the literature about hearing loss is considerably more limited and is often based on relatively small samples (frequently less than 100 individuals) and anecdotal evidence. In conducting its literature searches and reviews for this chapter, when possible the committee focused on articles that were relatively recent—less than 15 years old—because of the natural evolution in attitudes and beliefs that are often associated with advances in technology, changes in education, and shifts in societal norms.

INDIVIDUALS AND FAMILIES

Living with hearing loss or having a loved one with hearing loss, especially when the loss is severe or untreated, has the potential to affect many aspects of everyday life and can be associated with a diminished quality of life (see Chapter 2). Hearing loss has been associated with serious health comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem and insecurity, social isolation, stress, mental fatigue, cognitive decline and dementia, reduced mobility, falls, and mortality (see Chapter 2). As described in earlier chapters, both the severity of hearing loss and the impact that hearing loss has on individuals’ lives vary. These variations combined with numerous individual-specific factors (e.g., environment, available support, attitudes, preferences, or socioeconomic status) create unique circumstances for each person with hearing loss. Recognizing these individual circumstances and empowering individuals and their families to take action and to become familiar with the full range of options for managing hearing loss is fundamental to maximizing quality of life and ensuring that individuals with hearing loss and members of their families have every opportunity to thrive. Individual empowerment should be built on a foundation of awareness, education, and support, where individuals and families play a central role within a constellation of other entities across the social-ecological model (see Chapter 1), including health care providers, employers, advocacy organizations, communities, and the public—all of which can contribute to empowerment.

Attitudes and Beliefs

People with hearing loss may perceive and experience a range of feelings and emotions about hearing loss, seeking care, and using such technologies as hearing aids. Negative attitudes and beliefs about hearing loss can originate both internally—arising from the beliefs and attitudes of the individual experiencing the hearing loss—and externally—produced by the beliefs and attitudes held by various social connections, including family members, friends, health care professionals, employers and coworkers, the general public, and the media. When considering how hearing loss may affect self-perception and social identity, many individuals cite fears of feeling or being perceived as old, frail, less capable, vulnerable, uninteresting, unattractive, or less desirable or as having a disability or cognitive impairment (Habanec and Kelly-Campbell, 2015; Kochkin, 2007b; Munro et al., 2013; Southall et al., 2010; Wallhagen, 2010). Because of these perceptions, people may hide their hearing loss or deny that it affects their lives, may opt not to seek treatment, or may choose not to use hearing aids after they have been purchased.

Similar to many other health conditions, attitudes and beliefs about hearing loss are directly linked to behavior (Glanz et al., 2008; van den Brink et al., 1996). Studies of older adults have demonstrated that hearing loss is often accepted as a natural part of aging that does not require intervention and that individuals often believe that hearing aids are not effective or that they only marginally benefit the user (Kochkin, 2000; McCormack and Fortnum, 2013; Ng and Loke, 2015; Oberg et al., 2012; van den Brink et al., 1996). As discussed in Chapter 4, there are numerous reasons why individuals choose not to adopt or use hearing aids or choose not to seek hearing health care. One notable factor is attitude. In a market survey, Kochkin (2007b) found that attitudes and stigma played a sizable role in decisions about hearing aid adoption. Two-thirds of survey respondents reported negative attitudes that resulted from problems with hearing aid performance, and almost half chose not to use a hearing aid due to some form of perceived stigma; respondents specifically noted embarrassment, pride, and fear of being viewed by others as old or frail or as having a physical or mental disability (Kochkin, 2007b).

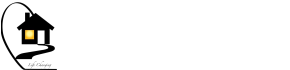

In a longitudinal study of experienced and reinforced stigma among older adults with hearing loss and their communication partners,1Wallhagen (2010) developed a model of the interaction between three primary areas of experienced stigma—self-perception, ageism, and vanity—and reinforced stigma (see Figure 6-1). The specific attitudes and beliefs that are described converge and affect decisions about whether to be evaluated for hearing loss, to seek treatment, and to use hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies. These types of beliefs, misperceptions, and stigmas, in combination with other barriers described earlier in the report (e.g., affordability, accessibility), can directly hinder action and timely access to the kinds of high-quality care and community-based services that can help greatly to optimize quality of life and overall well-being.

The attitudes and beliefs of spouses, partners, family members, and friends are also highly influential in decision making and can either help to overcome or reinforce the perceived stigma associated with hearing loss and the use of hearing aids and other technologies. Positive attitudes and beliefs of partners and family members, along with greater levels of family support, have been associated with seeking help for hearing loss, the successful adoption and use of hearing aids, and increased self-efficacy in the use of hearing aids (Dawes et al., 2014; Hickson et al., 2014; Meyer and Hickson, 2012; Meyer et al., 2014; Ng and Loke, 2015). In fact, Hickson and colleagues (2014) concluded that the strongest indicator of positive outcomes for hearing aid use was having the support of family, friends, and significant others. Conversely, negative attitudes of family members—such as perceptions of old age, disability, and poor aesthetics—contribute to delays in disclosing

SOURCE: Adapted from Wallhagen, 2010. Reprinted with permission of Oxford University Press.

Although experienced and perceived stigma can prompt delays in disclosing hearing loss and seeking assessment and treatment (Clements, 2015; Southall et al., 2010; Wallhagen, 2010) (see Figure 6-1), not everyone manages stigma and negative attitudes in the same way. Some individuals tend to have more positive attitudes and to be more resilient and are able to overcome the effects of stigma by pursuing positive opportunities, learning new skills to manage the hearing loss, and seeking out interactions with others who have hearing loss (Shih, 2004; Southall et al., 2010; Wallhagen, 2010). Some individuals look within their social circles for support or focus on the possible benefits that treatment can offer. Studies demonstrate that, among other factors, people with more positive attitudes and expectations are more likely to be empowered to take action and experience success with treatment options such as hearing aids and communication programs (Laplante-Lévesque et al., 2012b; Ng and Loke, 2015; van den Brink et al., 1996). This ability for some to thrive in spite of perceived stigma presents an opportunity for educating others and fostering resilience among individuals with hearing loss. Resilience and educational interventions, for both individuals with hearing loss and their families, should be studied in greater depth in order to develop and evaluate techniques and adaptable programs that can encourage resilience and enable individuals to overcome barriers and take action in communities across the country.

Health Literacy and Understanding Hearing Loss

Health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Ratzan and Parker, 2000, p. vi). It was elevated to a national public health priority following the 2000 release of the goals and objectives for the Healthy People 2010 initiative and the release of the IOM report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion in 2004 (HHS, 2000; IOM, 2004). Adults more than 65 years old; racially and ethnically diverse populations, especially Hispanic adults; people with lower socioeconomic status (i.e., lower levels of education and income); and people with disabilities all tend to have lower levels of health literacy, as do more men when compared with women (Kutner et al., 2006; NCHS, 2012). In recent years, health literacy researchers have uncovered various serious consequences of low health literacy, such as poor health outcomes and overall health status, declines in physical function among older adults, decreased access to and use of health care services, and increased health disparities among racially and ethnically diverse populations (e.g., Bennett et al., 2009; Berkman et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2015b). The IOM’s 2004 report concluded that increasing health literacy is a shared responsibility, “based on the interaction of individuals’ skills with health contexts, the health-care system, the education system, and broad social and cultural factors at home, at work, and in the community” (IOM, 2004, p. 35).

Despite the national focus on increasing health literacy, few studies have examined the role of health literacy on hearing health care or the impact it may have on the uptake of and adherence to various treatments. Nair and Cienkowski (2010) identified a clear mismatch between the literacy levels of individuals with hearing loss and the language that audiologists used during consultations and also the language used in written hearing aid user instructional brochures produced by manufacturers and given to individuals purchasing hearing aids, as mandated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Caposecco and colleagues (2014) conducted a review of 36 hearing aid user instructional brochures and determined that 25 of them (69 percent) were not suitable for older adults because of the terminology, technical vocabulary, and jargon used. The authors also identified deficiencies with the scope of the content and the layout/typography. Another recent review of a modified hearing aid user instructional brochure, which was developed using best practices in health literacy (e.g., the use of graphics, lower-level vocabulary, and increased font size), found that people who were given the modified brochure performed better on a test of hearing aid management and were able to complete more hearing aid operation tasks without assistance than those who were given the manufacturer’s brochure (Caposecco et al., 2016). In addition to the FDA-mandated provision of user instructional brochures, some manufacturers and hearing health care professionals provide customized information on specific hearing aids and other technologies in order to better guide and educate consumers. However, the written information provided during consultations may vary widely in content, depth, and health literacy scores.

Atcherson and colleagues (2013) found that audiologists may not be aware of the extent of low levels of literacy and health literacy in the United States and that they may also be unaware of the discrepancies between literacy rates and the written materials that are often presented to patients (e.g., consent forms, privacy forms). The American Academy of Audiology’s Standards of Practice calls for audiologists to develop and use language and written materials that are at appropriate heath literacy levels (AAA, 2012). When communicating with individuals with hearing loss and their families, there are numerous other communication factors that audiologists and other health care professionals need to be aware of if they are to ensure

effective communication and comprehension. For example, self-efficacy and the comprehension of hearing terminology and hearing aid jargon may increase over time with experience. Therefore, an individual diagnosed with hearing loss or using a hearing aid for the first time may require a more simplified explanation than an individual who has been managing hearing loss and using hearing aids for many years.

An individual’s hearing loss in and of itself may create unique communication challenges for patients, regardless of the health care setting. The possibility that some individuals with hearing loss may not accurately hear some explanations and instructions may compound underlying barriers related to health literacy, further complicating the individual’s ability to understand and process information provided during hearing assessments and consultations, as well as during other interactions with the health care system (see Chapter 3). Furthermore, possible language barriers need to be considered when consulting with patients and their families. Appropriate and comprehensible communication, both written and verbal, is crucial to further empower people with hearing loss, increasing the likelihood of successful self-management of hearing loss and uptake of appropriate treatments.

Improving Consumer Measures

In considering how to improve health literacy and understanding about hearing loss for individuals and their families, the committee suggests that researchers explore the possibility of developing an easy-to-understand measure of hearing and hearing loss for patients. There is currently no simple, consumer-friendly measure in wide use, and the results of standard hearing evaluations, in the form of audiograms and other measures of hearing and communication, may be too complicated for some individuals with hearing loss to understand or retain. Although audiometric results are complex, the committee recognizes the importance of the pure-tone thresholds recorded on an audiogram as an important, basic measure of hearing acuity and urges efforts to determine ways to better convey this important information. One such example of a counseling tool in audiology is the familiar sounds audiogram, although there is potential for further simplification into a tracking metric.

Physicians and researchers have identified and developed numerous measures to assess, quantify, and improve health. Table 6-1 provides examples of commonly used health measures and indicators. Although some consumers may not fully understand the underlying principles and physiological mechanisms of these measures, the measures provide individuals with a discrete number, usually associated with a range of outcomes (e.g., normal, at risk, high), that can be used to better understand risk factors and

TABLE 6-1

Examples of Health Measures That Are Available for Individuals to Easily Track and Monitor Changes in Their Health Status

| Measure/Test | Testing Methods and Use |

|---|---|

| A1C | A1C levels are determined through a blood test and offer an average measure of blood glucose levels during the prior 3 months. A1C can be used to help identify and diagnose diabetes and pre-diabetes. Levels can be measured periodically to identify changes in blood glucose and to determine whether treatments and lifestyle changes are effective for individuals with diabetes (NIDDK, 2014). |

| Blood pressure | Blood pressure can be measured using an automated blood pressure cuff or with a cuff and a stethoscope. It is reported with two numbers: systolic, the pressure in the vessels when the heart beats, and diastolic, the pressure when the heart is at rest. Blood pressure measures are divided into three categories—normal, at risk (prehypertension), and high—and can be used to determine risk for heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease (CDC, 2014). |

| BMI | Body mass index (BMI) is an estimated measure of body fat, which is calculated by dividing a person’s weight by his or her height and squaring that number. The BMI scale is usually divided into four categories—underweight, normal, overweight, and obese—and it can be used to assess risk for health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, some types of cancer, and other conditions associated with obesity (CDC, 2015a). |

| Visual acuity | Visual acuity tests are administered using standardized vision charts. Visual acuity is frequently expressed as a fraction: The top number is the distance of the patient from the eye chart (usually 20 feet) and the bottom number is the distance away from the chart that a person with normal vision would need to stand in order to read the same line correctly as the person being tested. The test can be used to measure changes in vision over time and identify possible eye conditions that may need further treatment (NLM, 2016). |

more easily track changes in their health over time. These specific measures also provide a simplified starting point for discussions between individuals and health care professionals about opportunities to improve health and well-being and may contribute to improved hearing health literacy.

The American Heart Association and health care systems across the United States have leveraged specific health metrics through Know Your Numbers campaigns in order to educate individuals about diabetes and about risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as obesity, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure. These education initiatives encourage individuals with pre-diabetes and diabetes to track their weight and body mass index, blood sugar levels, cholesterol, and blood pressure (AHA, 2015; BCBS of Nebraska, 2016; Johns Hopkins University, 2016). In Australia, researchers developed a community-based Know Your Numbers intervention that focused on educating consumers in pharmacies about high blood pressure and other risk factors for stroke. Three months after measuring the participants’ blood pressure and providing educational resources, knowledge about hypertension and its risk factors improved across the study population (Cadilhac et al., 2015). A similar consumer measure is needed for hearing.

An easy-to-remember consumer measure could be generated from the results of pure-tone audiometry, but a simplified, real-world measure of communication abilities could also be beneficial in providing consumers with understandable and realistic results. For many years, researchers have suggested that measuring speech recognition in noisy backgrounds has substantial benefits over the traditional assessment, which involves measuring speech recognition using lists of simple words that are presented at relatively high volumes in a quiet background (e.g., McArdle and Wilson, 2008; Smeds et al., 2015; Wilson, 2011). McArdle and Wilson (2008) argued that testing speech recognition in the presence of noise offers four primary advantages, including

- better alignment with the most common concern of people with hearing loss—understanding speech in noisy or complex acoustic environments;

- a more accurate assessment of the impact of hearing loss in real-world settings;

- informing the selection of the most appropriate hearing technology given individual needs; and

- helping set expectations regarding hearing aids and their performance in real-life situations.

Box 6-1 provides examples of hearing tests that were designed to measure speech recognition in noise by presenting the listener with sentences or words in the presence of various types and levels of background noise. Primarily, there are two types of tests that measure speech recognition in noise. The first uses fixed levels of speech and noise, with the outcomes reported as a percentage of words or sentences repeated correctly (i.e., 0–100 percent). In the second type, known as an adaptive procedure, the speech or noise levels, or both, are adjusted depending on the response of the listener, and the outcomes are reported in terms of signal-to-noise ratio in decibels (dB SNR). This ratio represents the difference between the level of speech and noise that is required for an individual to understand 50 percent of the words or sentences presented during the test. Evidence-based reference standards for dB SNR results have been established through tests of large numbers of people with normal hearing.

These standards serve as a point of comparison for dB SNR measures for people with hearing loss, and they can provide an assessment of the ability to understand speech in noisy environments.2 As part of a consultation with a hearing health care professional, these results—along with the pure-tone audiogram, which is a measure of hearing acuity—could provide a more comprehensive assessment of how individuals might function in real-life settings, which are frequently filled with background noise (e.g., restaurants, classrooms, offices with an open design, public transportation, sports arenas, gatherings of friends and family), and how hearing technologies and auditory rehabilitation may be used to improve communication. Although these tests do exist and have been validated in some cases, little is known about how frequently they are employed during hearing assessments and consultations.

The exploration, development, and widespread application of easy-to-understand and real-world tests of hearing loss could provide a basis for moving beyond the current focus on the audiogram. Additionally, a consumer-friendly measure, particularly if it were tied to outcomes of real-world tests, could be used to promote regular hearing assessments for those who have questions about changes in their hearing and would enable individuals to more easily monitor changes in their hearing over time, potentially reducing confusion about hearing loss measures and empowering individuals to seek treatment. These types of easy-to-understand tests and measures could also be used to realistically set expectations and demonstrate the effectiveness of hearing aids in more realistic listening environments to individuals and their families so that they can compare them to un-aided hearing in those environments.

For example, a result of –5 dB SNR indicates that the speech level was 5 dB lower than the noise level in order to correctly identify the words or sentences 50 percent of the time, which is a standard result for an individual with normal hearing. A +5 dB SNR indicates that the speech level had to be 5 dB higher than the noise level in order to achieve the same 50 percent correct score. This dB SNR outcome is considered poorer compared to someone with normal hearing and may be typical of some individuals with hearing loss.

In order for consumers to obtain, process, and understand information relevant to hearing loss treatment options, easy-to-understand, evidence-based information needs to be readily available and presented by health care professionals following a diagnosis of hearing loss. Given the assortment of hearing aids and assistive technologies on the market, the decisions that individuals must make regarding which type of services or product will best meet their needs, preferences, and budgets can be overwhelming, and they are further complicated by marketing materials that do not meet health literacy standards. Currently, there are few independent information sources available to consumers that would allow easy comparisons across hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies. Furthermore, the lack of standardized terminology between manufacturers about the features and capabilities of these technologies makes comparisons even more challenging (see Chapter 4).

Consumer Reports recently issued a consumer’s guide to buying hearing aids that offers advice on factors to consider when purchasing a hearing aid. However, the guide does not feature a head-to-head quality comparison across brands, as has been done with other consumer products (Consumer Reports, 2015). In an effort to better guide consumer decision making, the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) developed a consumer checklist that provides individuals and their families with questions to ask when purchasing hearing aids (HLAA, 2016c). However, additional efforts are necessary in order to provide consumers with information that is easy to understand, fulfills health literacy requirements, and uses standardized terminology to describe hearing aid features. Consumer information on hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies should be made available through independent websites and other media. To ensure that consumers have the necessary tools to make informed decisions, websites with this information should include the following:

- comprehensive descriptions of the full range of hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies available and their features, including connectivity options and requirements; and comparative data on technical traits and differences, clinical traits and performance variations, and practical traits, such as variations in features, connectivity, and costs.

Empowering Individuals and Families through Education and Support

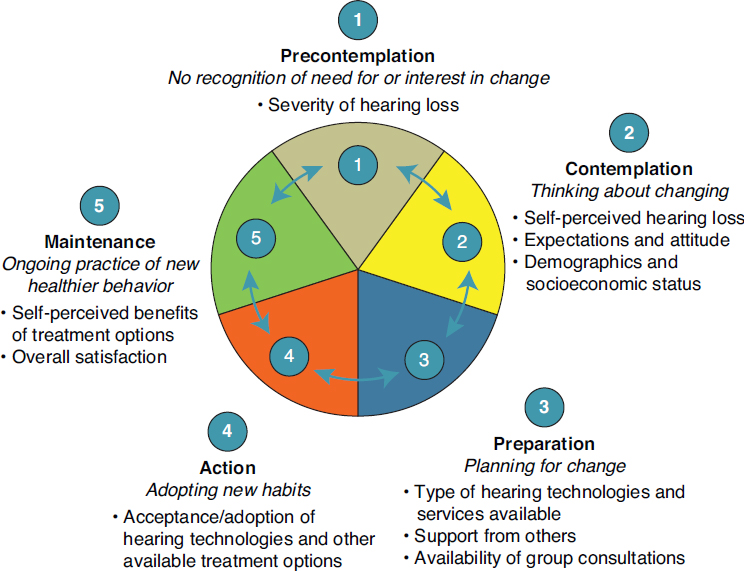

The path toward the recognition of hearing loss and the seeking of treatment can be influenced by numerous factors and will vary from one person to the next. Still, that path will often follow the transtheoretical model, also known as the stages-of-change model (see Figure 6-2). Since its development in the 1980s, the transtheoretical model has been applied to numerous public health concerns including smoking cessation, substance use, weight loss and obesity, cancer screening, HIV/AIDs testing, and medication compliance, and it has also been applied in the hearing loss literature (e.g., Laplante-Lévesque et al., 2012b, 2013, 2015; Ng and Loke, 2015; Saunders et al., 2012). Ng and Loke (2015) hypothesized that factors such

SOURCES: Adapted from Ng and Loke, 2015, and Prochaska and Di Clemente, 1982. Reprinted with permission from Taylor and Francis, Ltd. Copyright British Society of Audiology; International Society of Audiology; Nordic Audiological Society.

During the first stage, which can last up to approximately a decade, an individual begins to recognize and may admit to age-related hearing loss (precontemplation stage) (Davis et al., 2007). Even after a hearing loss is first recognized, it may take another period of time for that individual to seek assessment, diagnosis, and treatment (contemplation and preparation stages). Although the stages are somewhat fluid, the contemplation stage typically entails the individual confirming that the hearing loss exists, that it has an impact on everyday life, and that some action needs to be taken. It is also the phase in which the individual begins to consider possible actions and treatments options. During the preparation phase, the individual becomes poised to take action (e.g., talking more openly about the hearing loss with others, researching assessment and treatment options, making the first appointment). Active steps toward seeking assessment and diagnosis, as well as adopting a treatment option, represent the action phase. Following a diagnosis, some individuals may begin to wear hearing aids, use other assistive technologies, or participate in peer-support groups (maintenance phase), while others may choose not to take action (returning to the precontemplation and contemplation stages). Still others may decide not to use or maintain a hearing aid after it has been purchased (a breakdown in the action and maintenance stages).

The transtheroetical model exists within the broader social-ecological model that is described above and in Chapter 1. Numerous factors, external and internal, can influence an individual’s progression or regression through the five stages of the transtheoretical model. As described above, the attitudes and beliefs of the individuals and the support of family and friends play a role in an individual’s ability to recognize the problem, seek professional assistance, and use hearing aids and other technologies and services. Additionally, health care professionals, advocacy organizations, and the availability of community-based resources can also affect progress, both directly and indirectly. The specific individual needs, environment (e.g., living or working in a noisy environment rather than a quiet one), and preferences of the person will also affect progression through the model. There are times when an individual may be ready to take action but cannot because of a lack of resources or support at the health care system or community levels—challenges that are directly related to accessibility and affordability. Therefore, the committee reiterates the need for solutions at all levels of the social-ecological model that will in turn empower individuals to progress through the stages of change represented by the transtheoretical model and will ensure that care and support are readily available.

Community-Based Education and Support

Studies suggest that portions of medical information presented at the time of diagnosis can be misunderstood or quickly forgotten (Kessels, 2003; Martin et al., 1990; Reese and Hnath-Chisolm, 2005). Although written information presented at the time of a diagnosis can be helpful in many ways, information provided in that form may not be sufficient to address the personal adjustment and psychosocial elements of living with hearing loss. In order to effectively meet the needs and preferences of people with hearing loss and their families, education and support should not terminate in the professional office setting; it needs to extend into homes and communities, where it can be available when individuals are ready to absorb and operationalize it. Educational and support resources can take numerous shapes, from formal auditory rehabilitation programs in audiology clinics (see Chapter 3) to informal community-based support groups and self-guided resources provided by advocacy organizations. It is essential that health care professionals, particularly hearing health care professionals, are fully aware of what resources are available in their communities and reliably connect individuals with hearing loss and their families with those resources.

Community-based support resources and peer-support groups dedicated to hearing loss can promote resilience and provide resources for individuals with hearing loss. In recent years, the United Kingdom has increased its emphasis on community-based support services, some of which are specifically designed for hearing loss and may provide good models for supporting individuals and families. In order to respond to some of the growing demands on primary care providers and hospitals, the government of Scotland has set up community-based “sensory support centres” to deliver support services to individuals with hearing or vision loss (Smith et al., 2015a). Services provided include hearing aid fittings, mobility training, the installation of smoke alarm systems and doorbells designed for individuals with hearing loss, the provision of other assistive technologies such as telephones and alarm clocks, and instruction on how to use hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies. A review of one of the support centers in rural Scotland concluded that clients were satisfied with the services and levels of empathy shown in the providers. Additionally, individuals who used the services cited reductions in feelings of isolation and increases in self-confidence, self-esteem, and sense of safety.

In another study from the United Kingdom, Pryce and colleagues (2015) examined the role of volunteers in providing community-based peer support for people with hearing loss. The researchers found that volunteers can be used to bridge the gaps between audiology services and the community. However, the interactions were mostly limited to hearing aid maintenance and troubleshooting (e.g., cleaning, battery changes, re-tubing) and did not extend to psychosocial support and adjustment (Pryce et al., 2015). Despite the limited focus of the interactions described in this study, volunteers could be trained to provide greater support in psychosocial areas. For example, in previous studies (e.g., Brooks and Johnson, 1981; Norman et al., 1994) volunteers were trained to provide pre- and post-fitting counseling in an effort to set expectations, improve satisfaction, and increase the use of hearing aids among first-time hearing aid users. In addition to the use of volunteers for the provision of community-based support, ongoing studies are also investigating the possible role of community health workers in identifying and screening for hearing loss, as well as implementing community-based rehabilitation programs (see Chapters 3 and 5).

Peer-support groups can provide opportunities for individuals to connect with others who have hearing loss in order to share concerns, experiences, and strategies for coping with challenges in daily life, and these groups can foster resilience and restore social identity. The possible benefits and limitations of peer-support groups, including Internet- and phone-based groups, for other health conditions (e.g., cancer, diabetes, mental health) have been widely discussed in the literature, with mixed results (e.g., Campbell et al., 2004; Dale et al., 2012; Galinsky and Schopler, 2013; Griffiths et al., 2012). However, few studies have focused on peer-support groups designed for individuals with hearing loss and their families, and little is known about how prevalent or active such groups are throughout the United States. Many local chapters of HLAA (described below) offer peer-support groups led by trained volunteer leaders. Additionally, some state universities with speech and hearing centers and academic medical centers (e.g., Indiana University, 2016; University of Arizona, 2016) have established counseling or support groups, usually led by audiologists, where participants can share experiences and discuss the challenges of living with hearing loss. Cummings and colleagues (2002) reviewed a Web-based peer-support group for individuals and families. The researchers found that participants with less real-world support and less hearing loss were more active within the group, and those who were most active derived the most personal gains. The use of peer-support groups may offer a valuable mechanism for community-based education and support, but further research is needed to establish efficacy and determine best practices.

Advocacy organizations at the national and local levels can also play an important role in supporting those affected by hearing loss. In the United States, HLAA is a national membership and advocacy organization dedicated to improving communication access for people with hearing loss through education, support, and public policy and advocacy work. In addition to working at the national level, the organization has a network of approximately 200 state and local chapters. These chapters organize meetings, provide psychosocial support, make connections among people who have hearing loss, and offer education related to living with hearing loss and assistive services and technologies. Although most states have multiple local chapters, there are 13 states without a state or local chapter,3 leaving large geographic regions without access to these resources and supports (HLAA, 2016a).

In addition to HLAA, which covers a broad constituency of types of hearing loss, there are organizations that provide support to individuals with more severe hearing loss and deafness, such as the Association of Late-Deafened Adults, the National Association of the Deaf, the American Cochlear Implant Alliance, and TDI (formerly the Telecommunications for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, Inc.) (ACI Alliance, 2016; ALDA, 2016; NAD, 2016; TDI, 2016). A number of international organizations also are geared toward maximizing independence for people with hearing loss, such as Action on Hearing Loss and Hearing Link in the United Kingdom, Better Hearing Australia, and the Canadian Hard of Hearing Association (Action on Hearing Loss, 2016b; Better Hearing Australia, 2016; CHHA, 2016; Hearing Link, 2016). Although the resources and services offered through advocacy organizations certainly provide value, the reach and efficacy of available resources have not been studied.

As young adults with hearing loss transition from adolescence to adulthood, they may require focused community-based education and support. When they leave secondary school systems, where the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act ensures that they receive an education tailore to meet their needs, they must advocate for themselves and clearly express their needs, preferences, and rights. For youth with disabilities, including those with hearing loss, reviews of available literature and meta-analysis of data have identified small, but positive associations between specialized education and support (e.g., the development of self-advocacy skills, vocational education, and transition programs) and positive outcomes in employment and higher levels of educational attainment (Haber et al., 2016; Schoffstall et al., 2015; Test et al., 2009). In communities across the United States, vocational rehabilitation counselors can offer a blend of educational and support services for young adults to help them build the skills and knowledge needed to maximize success in workplaces, colleges, and universities (Schoffstall et al., 2015). Some communities and states offer summer programs to assist college-bound students with hearing loss in their transition (e.g., Marion Downs, 2016; RIT, 2016). Additionally, peer-support groups and advocacy organizations can provide community-based resources and play a supportive role to better prepare young adults for managing real-world challenges.

At the other end of the age spectrum, older adults may also need specialized education and support. Beyond the community-based education and support resources that are specific to hearing loss, Schneider and colleagues (2010) found that older adults with hearing loss, especially untreated hearing loss or more severe hearing loss, are more likely than those without hearing loss to use community support services, such as Meals on Wheels programs, community-based nursing services, and home care services. This study also found that these individuals had an increased reliance on nonspouse family members and friends for assistance with daily activities, including grocery shopping and household chores. In a 5-year follow-up, individuals with hearing loss—both hearing aid users and those with untreated hearing loss—relied more heavily on community services and nonspouse family or friend support, with increasing use seen by those with greater severity of hearing loss. The participants with hearing loss were more likely to report having low health status, having experienced a fall in the last year and having an impairment related to walking, vision, or cognition (Schneider et al., 2010). These comorbid health concerns combined with the hearing loss may contribute to the increase in demands for the services described in this study. Understanding the community services and support needs of older adults with hearing loss will be beneficial as communities prepare for aging populations that will include large proportions of individuals with hearing loss and other health concerns that could affect independence.

When faced with a health concern or a new diagnosis—including hearing loss—many individuals and their families turn to the Internet for information and support (e.g., Bundorf et al., 2006; Couper et al., 2010; Medlock et al., 2015; Purcell and Rainie, 2014). Additionally, health care systems are now employing the Internet as a means to facilitate patient education and self-management of chronic conditions. In the United States, Internet access has increased rapidly since the 1990s, with more than 87 percent of the population using the Internet as of 2014 and almost 75 percent of households having high-speed Internet as of 2013 (File and Ryan, 2014; World Bank, 2016). Despite high rates of overall access, there are still groups with lower levels of access, including older populations, people with lower levels of education and income, those who live in rural areas, and ethnic and racial minority populations, especially black and Hispanic populations (File and Ryan, 2014; Pew Research Center, 2014).

The methodologies used to study Internet and computer use among individuals with hearing loss vary, as do the findings. For the most part, studies have found that those with hearing loss use the Internet at a rate similar to that of the general public. However, some studies have found higher rates of Internet use among those with hearing loss compared to their age-matched peers without hearing loss or the general public (Barak and Sadovsky, 2008; Henshaw et al., 2012; Thoren et al., 2013). Despite these findings, Henshaw and colleagues (2012) found that Internet use among adults between the ages of 50 and 74 years was reduced among individuals with more severe hearing loss compared with those with mild to moderate loss. In another study of older adults with hearing loss ages 55 to 95 years, Moore and colleagues (2015) concluded that increasing age is often associated with lower computer literacy and self-efficacy, a finding that is also reflected in the older adult population in general, which tends to have lower rates of technology adoption and Internet use (Pew Research Center, 2014). All of these findings may change in the coming decades as baby boomers, who tend to be more tech savvy, grow older.

Individuals searching for information on hearing loss on the Internet can get tens of millions of results within fractions of a second. These results have varying degrees of relevance and reliability, and the sheer number can present a challenge in terms of identifying which Web-based resources can be trusted to provide evidence-based information. Health information from government agencies, national advocacy organizations, and health care systems offer a wealth of helpful information. However, reviews of the readability of hearing and hearing loss information on the Internet suggest that consumers would need between 9 and 14 years of education to comprehend the available information, representing a sizable mismatch when compared to average health literacy rates in the United States4 (Laplante-Lévesque and Thoren, 2015; Laplante-Lévesque et al., 2012a). Although readability is a fundamental factor in the comprehension of the information, Laplante-Lévesque and colleagues (2015) noted, “Readability is only one of the many prerequisites for successful . . . understanding, comprehending, and making good use of health information” (p. 287). Additional factors in the comprehension of information include usability, visual design, ease of navigation, searchability, reliability, compatibility with multiple Web browsers and devices, and accessibility. Box 6-2 presents examples of Internet resources on hearing loss.

Regardless of the type of information and the mechanism by which that information is provided, Internet-based resources must be written and presented at appropriate levels of literacy and usability to maximize comprehension by the target audiences. Health literacy and usability are imperative design factors, especially when the target audiences are older adults with hearing loss and other populations that may have limited Internet access and computer literacy. Since an emphasis on health communications was announced as part of Healthy People 2010, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and its agencies have released numerous freely available resources to encourage and facilitate public and private entities, such as advocacy organizations, nonprofit organizations, and health care systems, to simplify Internet-based health information. For example,

- Usability.gov is an HHS-sponsored website that provides resources and best practices for Web developers to make websites more accessible and user friendly (HHS, 2016b).

- HHS has published an online guide to health literacy and simplifying content to better meet the needs of the public (HHS, 2016a).

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Communications & Public Liaison has a webpage devoted to clear communication that features information on health literacy and cultural respect (NIH, 2016).

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a webpage and numerous resources devoted to health literacy and has created the Clear Communications Index, which is a tool to help plan and assess materials and resources that will be used for public communication purposes (CDC, 2015b).

The hearing loss community and advocacy organizations need to evaluate Internet-based resources, take advantage of available government resources,

and implement strategies to optimize the information and educational materials on hearing and hearing loss for individuals and their families. Additionally, health care professionals need to be aware of the available online information sources and resources, and they should discuss the wide range of resources with their patients to ensure that people with hearing loss and their families are directed to reliable, evidenced-based information.

THE ROLE OF COMMUNITIES

Individuals and families are intrinsically woven into their communities, as is indicated in the social-ecological model. Communities are complex social structures where all people live, work, socialize, learn, and play. Most of the topics discussed throughout this chapter touch on community

in one way or another. This section focuses on workplace environments and the built environment. Although these factors are vital to supporting and encouraging participation for people with hearing loss, these environments are not always designed specifically for people with hearing loss and may require some form of modification or education to fully support people with hearing loss. This section also provides a high-level overview of the protections and opportunities that are offered by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which was signed into law in 1990 and revised in 2009.

Employers and the Workplace

Communication is necessary in the vast majority of jobs and career paths, whether it involves communication with a client or a coworker in a conference room or it ensures an employee’s safety in a factory or industrial setting. In recent decades the profile of workplaces and workers has changed; more jobs than ever are found in office settings, and individuals are remaining in the workforce longer, increasing the likelihood that hearing loss could affect interactions and relationships with coworkers, job performance, promotion potential, and overall employment opportunities at some point in workers’ careers (Munro et al., 2013). Despite the enactment and revision of the ADA, which provides a series of protections for employees (see Box 6-3), individuals with hearing loss may continue to experience stigma, unfavorable attitudes, employment disadvantages, and overt or perceived discrimination in the workplace. For example, among 174,610 allegations of discrimination filed with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under Title I of the ADA between 1992 and 2003, Bowe and colleagues (2005) found that almost 9,000 complaints had been filed by individuals with some degree of hearing loss. Additionally, a study by McMahon and colleagues (2008) concluded that of the discrimination claims they studied, hearing was the second most cited reason—after back problems—for claims related to hiring decisions.

The perceived attitudes and beliefs of coworkers, supervisors, and employers have been cited as reasons for employees not disclosing their hearing loss, not seeking accommodations in the workplace, and delaying assessment and treatment for hearing loss (Clements, 2015; Kochkin, 2007a; Southall et al., 2011). However, as described earlier, not everyone perceives or responds to stigma in the same way. The majority of participants (70 percent) in focus groups5 conducted by Tye-Murray and colleagues (2009) had disclosed their hearing loss in the workplace, and many described positive interactions with and support from coworkers, supervisors, and employers. The participants in this study maintained positive, “can-do” attitudes; had used effective coping mechanisms; developed the resolve and stamina to overcome barriers; and noted that hearing loss was becoming more commonplace in professional employment settings because of the aging baby boomer generation (Tye-Murray et al., 2009). In part, these employment experiences can be attributed to supportive relationships and environments—beneficial factors that are often associated with positive outcomes and resilience. These positive experiences are encouraging and lead to the question of how to ensure these types of experiences become the norm in workplaces across the United States.

Although Tye-Murray and colleagues (2009) suggest that stigma associated with hearing loss in the workplace has declined, perceived stigma is still a concern. Further reducing stigma, fostering a supportive environment in the workplace, and developing coping mechanisms and resilience among employees with hearing loss are crucial steps to eliminating discrimination, promoting broader support in the workplace, and enabling employees to remain in the workforce longer, if they so choose. These steps are also necessary to encourage and empower employees to see the value in seeking assessment and treatment for possible hearing loss rather than hiding it and possibly allowing it to interfere with performance, employment, and career opportunities. Some auditory rehabilitation programs (see Chapter 3) include instruction on assertiveness and communication strategies, which can be beneficially applied in the workplace. A group-based rehabilitation program evaluated by Habanec and Kelly-Campbell (2015) encouraged people with hearing loss to be assertive in the workplace in order to ensure that their communication needs were being met, that effective communication strategies with the employer were being used, and that employees were aware of their rights and employer obligations under the ADA.

Additionally, people with hearing loss need to receive information from health care and hearing health care professionals as well as from employers about the accommodations that are available, the protections that are afforded by the ADA, and the resources that are available through the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in the event that workplace discrimination does occur (e.g., EEOC, 2015). This type of information is also important for young adults as they transition from an academic setting to join the workforce and begin to navigate various workplaces and career paths for the first time. On the employer side, human resources professionals and hiring supervisors need to have information on what are reasonable accommodations for hearing loss and how to acquire them; and tools for interviewing, hiring, working with, and supporting people who have hearing loss.

Built Environment and Universal Design

The acoustic profile of community and personal spaces in which people live, work, learn, and gather determines the atmosphere and functionality of those locations just as much as other aspects of structure and design. For people with hearing loss, the availability of hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies, acoustics, and the connections to other communications systems (see Chapter 4) may mean the difference between participating in conversations and engaging with their surroundings and feeling isolated. For the purposes of this report, the built environment refers to public and private spaces within a community that can be designed or altered to improve the experience for people with hearing loss through enhanced acoustics and accessibility. The committee believes that the built environment is an intrinsic part of addressing hearing loss and one that represents a major opportunity where solutions at many levels of the social-ecological model can be used to further empower people with hearing loss and enhance listening conditions for everyone. This is a broad topic with a number of ongoing efforts.

In addition to providing individuals with hearing loss meaningful protections and accommodations within the workplace, the ADA also includes provisions for the built environment. Title II (local, state, and federal government facilities) and Title III (places of public accommodation and commercial facilities6) of the ADA were designed to make public spaces more accessible for people with disabilities, including individuals with hearing loss. Additionally, section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and its subsequent amendments, requires that programs that receive federal funding provide accommodations in order to ensure effective communication. These laws emphasize that communication with individuals who have a disability must be equivalent to those without a disability, and thus auxiliary aids or services should be provided whenever requested and feasible. Examples of communication services and technologies for individuals with hearing loss may include the following:

- written materials, exchange of written notes, or the availability of note takers;

- real-time, computer-aided transcription;

- amplifiers and hearing aid–compatible telephones;

- open and closed captioning, as well as closed captioning decoders;

- various telecommunication systems (e.g., captioned telephones, video phones);

- videotext screens and displays;

- secondary auditory programs; and

- other assistive technologies or systems.

When a government facility, school, or business is unable to provide a requested aid or service because of financial limitations, the law requires that other forms of assisted communication be offered to ensure that the person with hearing loss understands what is being said and can communicate effectively (ADA National Network, 2014). The committee emphasizes the importance of these laws in ensuring that all students with hearing loss (from kindergarten through post-doctoral programs) regardless of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or geographic location have access to communication aids and assistive services in schools and universities, thus giving them an equal opportunity to learn; to actively engage with their peers, teachers, and professors; and to thrive.

In 2010 the Department of Justice released revisions to ADA regulations that included the ADA Standards for Accessible Design. The standards outline specific minimum requirements that are enforceable for newly designed or renovated public spaces as defined under titles II and III (DOJ, 2016). For example, sections 219 and 706 of the document provide standards and requirements for the implementation of assistive systems, and sections 215 and 702 describe requirements for fire alarm systems (DOJ, 2010). Acoustic design in the built environment has been a point of consideration for advocacy efforts and guideline development for decades with mixed results. For example, in 1993 the U.S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board—now called the U.S. Access Board—commissioned a report to provide guidelines for designated quiet areas in restaurants. The purpose of the quiet areas was to allow people with hearing loss to enjoy the experience of dining out while more easily interacting and communicating with other people around them.7 However, these guidelines have not been endorsed or implemented broadly. The availability of design standards and guidelines is a valuable step to strengthening the built environment and ensuring equitable accessibility. However, it is the consistent prioritization, application, and enforcement of evidence-based standards and guidelines that is needed in order to make real differences in the coming decades. Box 6-4 provides additional examples of current design standards and guidelines that are relevant to creating favorable acoustic environments and greater accessibility for people with hearing loss.

As discussed in Chapter 4, hearing assistive technologies include systems that employ transmitters, receivers, and coupling technologies to connect listeners to the source of sound via technologies such as wired devices (e.g., receivers with headsets), induction loops, or infrared or radio technologies (DOJ, 2010). These systems may also include technologies such as Bluetooth and will likely encompass emerging technologies as they become available. The installation of induction loops (also referred to as hearing loops) are an example of one type of hearing assistive technology that can be integrated into the built environment and has been described in various news outlets recently (e.g., National Public Radio, The New York Times, and Scientific American) (Hearingloop.org, 2015). As described in Chapter 4, when installed within a public space, induction loops can be paired with hearing aids and cochlear implants that have embedded telecoil technology to directly receive the transmission from the sound system. While this pairing requirement may be a limiting factor for those without hearing aids, hearing loops have been installed in a variety of public spaces, including theaters, museums, airports, sports arenas, classrooms and audi-

toriums, places of worship, and other large venues. However, the use of this technology is not limited to large public venues, as it can also be installed in private homes and on other smaller scales (Shaw, 2012). Current efforts to further expand the use of hearing loops in public spaces include installation in subway booths by the New York City Metropolitan Transit Authority and in taxicabs, post offices, and banks in the United Kingdom (Myers, 2010; Shaw, 2012). Further efforts to provide hearing assistive technologies and ensure compatibility among assistive technologies and across other communications technologies (e.g., phone, emergency alert systems) are critical (see Chapter 4).

In addition to the availability of hearing assistive technologies and services, the built environment can also be augmented to permit an optimal acoustic environment that benefits all individuals, regardless of hearing ability. Universal design is a concept that calls for environments and products to be designed so that they are “usable by all people to the greatest extent possible” (Mace et al., 1991, p. 2). The researchers who conceived universal design believed that the solutions should be of little or no cost and should simplify everyone’s lives. Sidewalk cutouts are a prime example of a universal design element: There is little or no additional cost associated with the cutouts, and they benefit people who use wheelchairs, scooters, walkers, and canes, as well as people pulling luggage, pushing strollers, riding bikes, or using wheeled dollies. In terms of improving the acoustic environment to benefit those with hearing loss and the general public, universal design elements could include installing noise-dampening panels, insulation, floor covering/carpet, and plush furnishings; diminishing excessive background noise whenever possible; optimizing reverberations; and configuring floor plans and workspaces to enhance acoustics (CHHA, 2008). The committee urges the development, evaluation, and implementation of design elements that can optimize acoustics in public spaces whenever possible, with an emphasis on universal design solutions. Additional work in the arena of universal design and the built environment in terms of ameliorating the effects of hearing loss is also needed.

PUBLIC EDUCATION AND AWARENESS

Society is the all-encompassing level of the social-ecological model within which all other activities occur. At this level, laws, regulations, policies, culture, and social norms shape solutions that are implemented at community and organizational levels, which then affect individuals with hearing loss, their families, and their social networks. The public, broadly speaking, also resides at this level. This section will explore public attitudes toward and understanding of hearing loss. It will consider how the media, public awareness campaigns, and advocacy efforts can be used to better educate the public, thus building a more supportive society and public experience for people with hearing loss. Although large-scale, nationwide initiatives that are designed to influence the public can be expensive; time consuming; requiring of multipoint stakeholder partnerships; and challenging to plan, execute, and measure, the solutions at this level arguably offer the potential for the largest impact and benefit to the most people.

Public Attitudes and Understanding

Changing public attitudes and understanding represents another opportunity to reduce the stigma that individuals with hearing loss experience. Although a few studies and targeted surveys have reported a positive evolution in public attitudes (described below), some literature suggests that individuals with hearing loss can be deemed by others as being old, socially inept, less friendly, cognitively impaired, or poor communication partners (Clements, 2015; Erler and Garstecki, 2002; Wallhagen, 2010). For example, when people respond inappropriately to verbal cues or do not respond at all, those people may be mistakenly perceived as being confused or being disengaged from or disinterested in their surroundings, when in fact the person did not hear the cue. Although negative public attitudes and stigma are serious concerns and can have a strong impact on the attitudes, beliefs, and decision making of people with hearing loss, interviews of people with hearing loss and targeted surveys suggest that public perceptions might be improving (AARP and ASHA, 2011; Rauterkus and Palmer, 2014; Wallhagen, 2010). This shift may be a result of an increased awareness and acceptance of disabilities in recent decades; the aging of the baby boomer generation, which is experiencing and openly discussing chronic, age-related health conditions and focusing on living well; younger generations that tend to have more tolerant views of individual differences; and advances in technology that provide individuals with new hearing and communication options.

Interviews of individuals with hearing loss suggest that there is an overall perceived lack of awareness and understanding about hearing loss among the general public (Southall et al., 2010). Surveys focused on noise-induced hearing loss shed some light on knowledge and understanding of this specific type of hearing loss. In a survey of university students and faculty, Shah and colleagues (2009) found that a large majority of participants (85 percent) expressed some concern about age-related hearing loss, and almost three-quarters (73 percent) were interested in learning about opportunities to prevent noise-induced hearing loss. However, participants cited a limited availability of information on hearing loss and prevention (Shah et al., 2009). Despite the possible gaps in available information, college students were generally knowledgeable about noise-induced hearing loss, with most participants correctly stating that this type of hearing loss could not be cured and was not reversible (Crandell et al., 2004; Shah et al., 2009). However, Crandell and colleagues (2004) found that young African American respondents were less likely to correctly answer questions about the reversibility of noise-induced hearing loss and symptoms related to excessively loud, potentially damaging noise. In considering these findings, the authors also noted that young African Americans were also less likely to report exposure to activities associated with risks for noise-induced hearing loss (e.g., motorcycle riding, racing cars, and listening to portable music devices).

The public also seems to be unaware of the difficulties and challenges that people living with hearing loss experience on a daily basis (Southall et al., 2010). Interviews focused on hearing loss in the workplace indicate that people do not necessarily know how to respond to or communicate with individuals who have hearing loss. Another commonly cited concern from these interviews was that colleagues tend to forget about an individual’s hearing loss and need to be reminded by the person with hearing loss. Table 6-2 lists basic communication strategies that can be used by friends, family members, coworkers, and the public to enhance communication with individuals who have hearing loss. Although many of these strategies target general interpersonal communication skills, they also offer the possibility of increasing comprehension and reducing frustrations.

Examples of Communication Strategies

| Strategy | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Speak face-to-face | When the speaker’s face is turned toward the listener, there is improved signal-to-noise ratio, and the listener uses facial cues to fill in the gaps that he/she may not have heard. |

| Reduce background noise | The ability to understand speech in the presence of background noise or distractors (e.g., television or restaurant noise) declines as a function of age, even for older adults without hearing loss. |

| Speak slower, instead of louder | When someone speaks loudly or shouts, it actually distorts the speech, often making it more difficult to understand. Also, shouting can make both the speaker and the listener more stressed. |

| State the topic | By making the topic of conversation clear at the beginning, the listener can more effectively use context cues to fill in the gaps. |

| Rephrase the statement | Repeating oneself becomes frustrating for the speaker and the listener. When the question or statement is rephrased, the listener has more context cues to fill in the gaps. In addition, some words are actually easier to hear, depending on the person’s hearing loss and the frequencies of the sounds in the word. |

SOURCES: Adapted from Mamo et al. (2016) and Marrone et al. (2012). Reprinted with permission from ASHA. Copyright 2012. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier. Copyright 2016.

During the committee’s third workshop, Zina Jawadi and Patrick Holkins, speakers for the panel that focused on the young adult perspective, described hearing loss as an invisible disability that is often misunderstood, noting that moderate hearing loss is especially difficult for the public to understand in comparison to deafness (Holkins, 2015; Jawadi, 2015). A general lack of understanding by the public can contribute to negative attitudes and can lead to stigma, which highlights the importance of public education efforts and campaigns that can reach diverse audiences through a variety of mechanisms.

The Role of the Media

Very little academic research exists on how hearing loss is represented in the media. Anecdotal experience and indirect references in the literature suggest that hearing loss is often portrayed as something comical in entertainment media (Foss, 2014; Noble, 2009). Cartoons, comic strips, television shows, and movies have depicted hearing loss using images that commonly involve an older person cupping his or her hand around an ear or using an ear trumpet, a person who completely misunderstands a conversation and responds inappropriately, or a person shouting at someone with some degree of hearing loss. The media uses these types of images as a comedic tool, in part, because most people have experienced amusing miscommunications due to a misheard statement, regardless of hearing loss; therefore, the audience can relate to these images to some extent. However, this type of comedy is not only insensitive to people who live with hearing loss, but it also reinforces public misperceptions and stigma associated with hearing loss.

A review of 276 fictional television shows originally broadcast between 1987 and 2013 examined how hearing loss has been portrayed in the media and why stigma has been perpetuated (Foss, 2014). The review focused on complete, start-to-finish storylines that featured characters who experienced hearing loss, most of which was sudden and due to an acute cause (e.g., foreign object, explosion, infection, magic). Therefore, this review did not capture all scenes or all images of hearing loss. The review found instances of hearing loss in 11 television shows over a total of 47 episodes. The characters that experienced the hearing loss were typically young, attractive professionals, and in the majority of cases (8 out of 11) the hearing loss was short-term and remedied by the end of the episode. A total of three characters experienced permanent hearing loss, with the loss being age-related in only one case. In all three cases, the character with permanent hearing loss adopted hearing aids, but there were no challenges with using the devices, there were no other accommodations or support needed, and the individual’s hearing was restored completely by the hearing aid—a combination of outcomes that is not very realistic. Despite many inaccuracies in the storylines studied, most characters denied the presence of their hearing loss and tried to hide it from their coworkers and friends—a reaction that is common in real life (Foss, 2014).

As discussed in the IOM report on the public health dimensions of epilepsy, a highly stigmatized health condition, the media portrayal of health concerns is an important tool for educating large audiences, increasing awareness, and possibly reducing stigma (IOM, 2012). In 2005 more than half of the respondents to the Porter Novelli HealthStyles survey reported that they learned new information about a health condition or disease through television dramas or comedies (CDC, 2005). Box 6-5 summarizes lessons that were highlighted in the IOM epilepsy report and the lack of storylines featuring hearing loss, especially age-related hearing loss, combined with the high prevalence of and overall misperceptions about hearing loss indicate that there is an opportunity for action. As concluded in the CDC’s analysis of the HealthStyles survey, “TV dramas/comedies serve a critical health education function when they provide accurate, timely information about disease, injury and disability in storylines for the vast majority of U.S. residents who watch at least a few times a month, and especially for 64% of the population . . . who are regular viewers watching

Such fictional portrayals of hearing loss are not the only media opportunity for educating the public about hearing loss; the news media can also play a role. One type of hearing loss that has been frequently discussed in the news media is noise-induced hearing loss (see Chapter 2). Concerns about the risks of hearing loss caused by loud noise became more prevalent with the widespread use of portable music devices starting in the 1980s (Peng et al., 2007; Punch et al., 2011). As researchers considered the effects of portable music devices on hearing, the news media began to highlight the risks of and prevention strategies for noise-induced hearing loss (NIDCD, 2015b). Although the available evidence regarding the link between portable music devices and noise-induced hearing loss is mixed and somewhat controversial, most experts agree that young adults should be educated on the topic and consider the intensity and duration of listening (Punchet al., 2011). In surveys of young adults through the MTV.com website, Quintanilla-Dieck and colleagues (2009) found that young people identified popular media as the most informative resource available for information on hearing loss and the prevention of noise-induced hearing loss, which highlights the opportunities for the media to reach various audiences. Social media efforts, often applied in association with public education campaigns (described below), may also contribute to educating the public, especially young adults, about hearing loss—both noise-induced and age-related hearing loss. The use and efficacy of social media to educate the public and increase awareness warrants additional investigation.

Marketing and Its Role in Educating the Public

Interviews and surveys of people with hearing loss suggest that many of them view hearing aids as a visual reminder of the stigma and negative attitudes and feelings about hearing loss that are described above (Dawes et al., 2014; Kochkin, 2007b; Laplante-Lévesque et al., 2010; Southall et al., 2011), and factors related to vanity and overall aesthetics are commonly cited as reasons why people choose not to adopt or use hearing aids (McCormack and Fortnum, 2013; Wallhagen, 2010). To combat these concerns, hearing aid manufacturers and marketers have focused on developing and advertising smaller, easy-to-hide hearing aids over the last three decades (Clements, 2015). Although advances in technology and size reductions may be credited for prompting individuals who are sensitive about the size and appearance of hearing aids to purchase and use them, the emphasis on these features in advertising—another form of media—may also be responsible for reinforcing negative public attitudes and stigma associated with hearing aids by implying that a small hearing aid is more desirable because it enables the wearer to hide his or her hearing loss (Wallhagen, 2010). This attitude can also magnify the perception of stigma for those for whom a small hearing aid may be challenging to use and thus a larger hearing aid is more appropriate (e.g., an individual who has trouble manipulating very small objects). Hearing aid advertisements commonly appear on television, in print media (e.g., magazines, newspapers), and in audiology clinics and physician offices, thus reaching—and possibly influencing—large segments of the population.

To better serve people with hearing loss, reduce stigma, and educate the public, the marketing for hearing aids and any hearing assistive technology should focus on individuals finding a solution that is effective, meets their needs, and helps them reconnect with family and friends, become more socially engaged, and continue to participate in their communities, rather than highlighting the ease with which an individual can hide his or her use of hearing aids or hearing assistive technologies. Kochkin and Rogin (2000) call for a shift in messaging that moves away from hiding the hearing aid and away from thinking of it as device to be sold and toward a message that technology can change people’s lives, enhance relationships and intimacy, and reduce stress.

Public Education and Advocacy Efforts

Education is one of the most effective mechanisms available to combat misperceptions and stigma and should be used to help address these types of challenges with hearing loss. Public awareness campaigns and other public education efforts have been used successfully in the public health sphere for decades. In many cases, campaigns focus on educating the public and promoting behavior change (e.g., smoking cessation, exercise, and physical fitness), while others are developed to increase awareness and encourage a clearly defined, achievable action (e.g., taking part in cancer screening or HIV/AIDs testing, stopping drunk driving, using seat belts) or are designed to increase public awareness, correct misperceptions, encourage normalization, and reduce the stigma associated with a specific health condition (e.g., mental health conditions, disabilities, or epilepsy).